Is it normal to talk in complete sentences by two years old? Is it normal not to talk at all until five? Here are some milestones for a normally developing child. But there are many variations on normal.

- Infants should begin turning their heads toward noises in their early weeks. Loud noises, like thunder or a nearby dog’s bark, should startle them. A mother’s or caregiver’s voice should soothe them.

- By the time infants are six months old, many are babbling, that is, making lots of meaningless sounds. They might be saying “da-da-da-da-da” over and over. Rarely is a child associating his own voice sound with meaning at this age, yet it has been done. It is also normal for a child not to be babbling at half a year. If he is curious about his world and smiles when he sees people and things he loves, or when he enjoys experiences, he’s probably developing normally. No need to worry.

- From six to twelve months, children love to mimic adults. If you wave bye-bye, the child will wave bye-bye. If you stick out your tongue, the child will stick out his tongue. If you talk a blue streak while looking at him, he might try to babble back. What he says isn’t important, but his efforts to babble are. Yet some perfectly normal children won’t babble yet.

- At around a year old some children begin saying meaningful words. Usually they are nouns like “dog” or “mom,” but “mine” and “no” are sometimes first words too. Children might gesture with their early words to add meaning. Between twelve and 18 months, children add new words and use them correctly, usually one at a time.

- Between 18 months and two years, children usually begin putting words together in tiny sentences, such as, “No, no Miss” or “Nana bye-bye.” However, some might be chattering in complete sentences by the time they are two, and carrying on meaningful conversations, almost always child-centered. Usually they combine gestures with speech for added meaning.

- By two, if a child is not talking, or if she depends almost exclusively on pointing or grunting, this could be normal behavior. But more likely it is a sign that the child should be seen by a speech pathologist for testing. Many school districts offer services for preschoolers with delayed speaking.

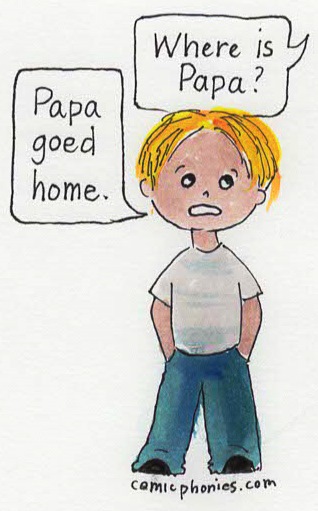

- However, at two years old it is normal for children to mispronounce words since they are learning vocabulary rapidly and might be mixing up certain words which sound similar. Or they might be tripping on sounds which are more difficult to say. If that happens, repeat the word properly in a reply to the child so the child can hear the word, but don’t focus on correcting the child. Mistakes are usually temporary.

- Between two and three years old, children develop larger vocabularies, adding a new word each almost daily. They add action verbs and adjectives. More and more they talk in small but complete sentences. They may leave out articles, yet they are picking up the rules of grammar (subject first, verb next; adjective first, noun next). You know they are learning grammar when they put the “d” sound at the end of irregular verbs to make the past tense, such as “Nana drived car,” or “I seed Daddy.”

- Some children stutter as they are learning to speak. This is not usually a problem for the child (unless someone makes fun of him) but it can be frightening for the parent. When this happens, resist your urge to think the sky is falling. Instead, slow down with your child, listen to him without interrupting, and never show any sign that his speech is abnormal. If it doesn’t subside in a month or two, then contact your pediatrician.

- Between three and four children should be speaking in small sentences. Their spoken vocabularies should continue to expand—more if they interact with well educated adults or if someone reads to them frequently. They should be using the past tense appropriately. Some children will be able to tell small stories and carry on simple conversations. Some will speak in much longer sentences and chatter nonstop. Even so, certain letter sounds might still be giving them problems.

- By four to five years old, children should be able to talk in sentences, to tell little stories, to repeat rhymes and to enjoy word play. If the child is struggling to speak, or if she refuses to speak, she should definitely be referred to a speech pathologist through the school system. Many school districts offer early education focusing on speech to such children.

- What if a child asks for help with words? Congratulations. Your child has learned that you can be trusted to help her learn. She will learn faster if she is willing to ask for help, so encourage her to ask questions. A child’s questions can drive a parent crazy, but asking you questions is your child’s fastest way to learn.

For more information, check out the work of Jules Csillag, a speech pathologist at http://www.julesteach.es. Also, online or in the library are many sources for normal child development, including language development.