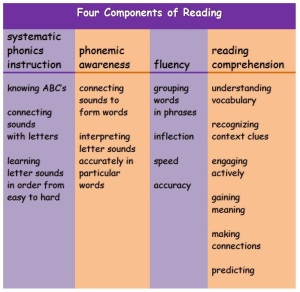

For years I have focused on the importance of a phonics-based reading curriculum for beginning readers. Research shows that young students exposed to sequential phonics instruction have better reading outcomes than students who learn primarily through other approaches.

But once students have learned the basic rules of phonics, and they are reading to learn new information, research shows other activities can help students comprehend better. Here are some.

Photos, drawings, sounds, videos and picture books can help students understand new-to-them concepts before they read about them. Providing students with rich background information can make acquiring new information easier. Students can fit new ideas into old ideas, or show how the new idea is the same or different from the old idea.

Venn diagrams are another way to do this. For example, to learn the relationship of math operations, students could see a Venn diagram like this:

The idea is to connect new information to information students already know. Stick figures showing two families’ with arrows from one person to another could show what nieces and nephews are.

Tables connecting what students know to what they don’t know can help. Here is how. Create a row of three sections. On the left, write a vocabulary word or concept students know. Leave the middle blank. On the right, write the new concept to be learned. Help students fill in the center by connecting the idea on the left to the new word on the right.

| my birthday |

important day in my life, hard to forget day, day I think about |

milestone |

| What I’m doing at different times all day long |

8 Pledge of Allegiance

8:15 reading class

9:15 snack

9:30 math class |

schedule |

We adults connect new concepts to what we know all the time. And, like students, if what we know is scant, we have a hard time learning the new concept. For example, I was reading a novel about a World War I soldier who was demobbed. What in the world is demobbed? I wondered. Attacked by a mob? Thrown out from a mob? I looked the word up, and found that demobbed means discharged from military service.

Okay, so how do I remember it? I know what a mob is, but in this case mob is short for mobilized, so that doesn’t help. I know what a mobile phone is though, so I pictured a soldier texting someone on his mobile phone to tell that he is discharged. Maybe he is throwing his hat in the air too. So connecting pictures to words and events is another method of comprehending.

Learning to read doesn’t stop with applying the rules of phonics. That is a vital start. Another vital aspect of reading is comprehension, a lifelong process.

The idea is to connect new information to information students already know. Stick figures showing two familie with arrows from one person to another could show what nieces and nephews are.

Tables connecting what students know to what they don’t know can help. Create a row of three sections. On the left, write a vocabulary word or concept students know. Leave the middle blank. On the right, write the new concept to be learned. Help students fill in the center by connecting the idea on the left to the new word on the right.

| my birthday |

important day in my life, hard to forget day, day I think about |

milestone |

| What I’m doing at different times all day long |

8 Pledge of Allegiance

8:15 reading class

9:15 snack

9:30 math class |

schedule |

We adults connect new concepts to what we know all the time. And if what we know is scant, we have a hard time learning the new concept. For example, I was reading a novel about a World War I soldier who was demobbed. What in the world is demobbed? I wondered. Attacked by a mob? Thrown out from a mob? I looked the word up, and demobbed means discharged from military service. Okay, so how do I remember it? I know what a mob is, but in this case mob is short for mobilized, so that doesn’t help. I know what a mobile phone is though, so I pictured a soldier texting on his mobile phone that he is discharged. Maybe he is throwing his hat in the air too.

Learning to read doesn’t stop with applying the rules of phonics. That is a vital start. Another vital aspect of reading is comprehension, a lifelong process.