To download 17 new Funny Pages go to Book Apps and Funny Pages.

You might notice that most of our blogs focus on how to apply educational theory to teaching your child to read.

But you might be thinking that our Funny Pages are just that—funny pages. In fact, they too apply educational theory to learning how to read.

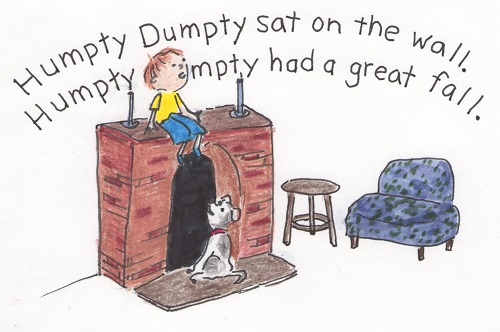

- Kids love humor. Our Funny Pages begin with humorous situations—a cat wearing a baseball cap and holding a bat, or a man running inside a can. Even if the child can’t read, he can enjoy looking at the silly pictures. We think of the silly pictures as our “Gotch-ya!” moment with the child.

- Our reading words are almost all one-syllable, short-vowel, CVC words. Nearly every method of teaching reading begins with these kinds of words because they are the easiest to grasp.

- Most of our Funny Pages begin with just one or two words (usually the subject) and build onto those words with another word or two, and then another, and another. The first line is repeated in the second line and then added to. For example:

- John can.

- John can go.

- John can go up.

- John can go up a hill.

By repeating words, there is less new information on each line, so the child can rely on what he has already learned and build on that.

- White space around words makes them look “friendlier” and less intimidating. So even though the first lines in most of our Funny Pages might have only one or two words, that white space after those words serves a powerful reading function: to relax the child and encourage her to read.

- We notice that so much beginning reading material is not “literature.” It uses easy-to-read CVC words, yes, but the words have little meaning because the grouping of words makes little sense. Sentences like “A cat bats a fat hat at Pat on a mat,” leave the child wondering what that sentence means. The words contrive to tell a story, but the child has to work hard to understand. We start not with the words but with the story—the silly art that lures children into the words because the art work is so funny. Then we add words to describe what is happening.

- Telling a story about wax in ears can be frustrating if we don’t use the word “ear.” Or telling a story about a girl falling down a hill can be daunting if we don’t use the words “fall” or “down.” But we have chosen to gear our Funny Pages to beginning readers, and to stick to simple CVC words that they can sound out successfully.

Do you have a beginning reader? We welcome your feedback on how they respond to our Funny Pages. We also welcome your child’s idea of a silly story for Mrs. A to illustrate. How would your little girl or boy like to see “Submitted by” and her or his first name on one of our funny pages? Send us your children’s ideas.