Wordless picture books are just what they seem to be—beautifully illustrated picture books without any words. Most tell stories with everything you’d expect from a story—a setting, characters, a plot, a crisis, and a resolution. Wordless picture books are a great way to teach reading and writing.

How can you use them to teach?

For a nonverbal toddler, show the pictures and ask the child to show what is happening by acting out the story. Let the child linger over the pictures to gain as much meaning as possible.

For a verbal preschooler who cannot write, show the pictures one at a time, and ask the child to tell you what is happening. To round out the child’s observations, ask questions about emotions shown, relationships of people and animals, and predictions of what will happen next. Ask if the story is scary or silly or serious.

For a child who can write a little, show the pictures and ask the child to write one sentence about each page. Focus on the content of the sentence. Encourage the child to figure out the main idea of a page and write about that. But remind about capital letters and punctuation.

For older elementary grade children, look at the pictures first. Discuss what happens at the beginning, middle and end. Ask about the setting (time and place), what problem needs to be solved, who is the main character/s, who or what opposes that character, and how the character overcomes the problem. Now ask the students to write an outline—not sentences, but words or phrases to remind the students what they want to include in the story. You might share a check list of elements to include. Now have them write the story.

For middle school students, show the story to them once for them to get the gist of it. Then ask the students to write (one word/phrase to a line) the following situations: exposition, inciting action, rising action, crisis, falling action, resolution. Review these words if students seem forgetful. Now show the pages of the book again, slowly, and ask the students to identify what happens in the book for each situation. When done, discuss the student choices and help students match the scenes in the book with the six situations. Now ask the students to write the story.

Where can you find wordless picture books? Search online or, if you have a children’s librarian at your school or public library, ask the librarian. Look for books with enticing illustrations that tell a story with a beginning, middle and end. Two of my favorites are The Fisherman and the Whale by Jessica Lanan and The Farmer and the Clown by Marla Frazee.

You can also use wordless films. A favorite of mine is La Luna by Pixtar.

I suggest you give your child a pretest to see what reading skills your child has learned well, and what ones he has not yet grasped.

The words on this pretest are more or less divided into four kinds of words in this order:

1. Short (closed) vowel, one-syllable words. These include one- and two-letter words, words beginning or ending with blends and digraphs (black, church) words which end in twin consonants (fell, jazz), words which end in “ck,” and words to which an “s” can be added to make plural words or certain verbs (maps, runs).

I suggest you give your child a pretest to see what reading skills your child has learned well, and what ones he has not yet grasped.

The words on this pretest are more or less divided into four kinds of words in this order:

1. Short (closed) vowel, one-syllable words. These include one- and two-letter words, words beginning or ending with blends and digraphs (black, church) words which end in twin consonants (fell, jazz), words which end in “ck,” and words to which an “s” can be added to make plural words or certain verbs (maps, runs).

2. Long (open) vowel, one-syllable words. These include words ending with silent “e,” words with double vowels which have only one vowel pronounced (goes, pear), and certain letter combinations (ild, old). They also include words with “oi,” “oy,” “ow” and “ou” letters.

3. Two– and three-syllable words which follow the above rules (catnip, deplete) and two- and three-syllable words which don’t follow the above rules but which follow a pattern (light, yield). These words include words with certain suffixes (le, ies) and words with a single consonant between two vowels (robin, motel).

2. Long (open) vowel, one-syllable words. These include words ending with silent “e,” words with double vowels which have only one vowel pronounced (goes, pear), and certain letter combinations (ild, old). They also include words with “oi,” “oy,” “ow” and “ou” letters.

3. Two– and three-syllable words which follow the above rules (catnip, deplete) and two- and three-syllable words which don’t follow the above rules but which follow a pattern (light, yield). These words include words with certain suffixes (le, ies) and words with a single consonant between two vowels (robin, motel).

4. Exceptions. These include words with silent letters (gnaw, lamb), words from other languages (debris, cello), and words which fit no pattern (business).

Ask your child to read the words in the pretest below. Each row across tests a particular phonics skill. If you child hesitates at all, that is the place to begin teaching him or her phonics. I will talk more about how to teach these four groups of phonics skills in my next blog.

Phonics assessment

bad, hem, fit, don, pug, am, if, lass, jazz

lock, Mick, bills, cliffs, mitts, catnip, Batman

grand, stent, frisk, stomp, stuck

chuck, shun, them, branch, brush, tenth

star, fern, birds, fork, purr, actor, doctor, victor

muffin, kitten, collect, pepper, gallon

complex, helmet, falcon, napkin, after

tantrum, muskrat, constant, fulcrum, ostrich

skate, bike, Jude, mole, dare, shore, tire, pure

need, cheer, aim, hair, bay, pie, boat, oar, Joe, low, soul

fruit, few, child, blind, fold, colt, roll, light, high

earn, worm, rook, pool

fault, claw, all, chalk, Walt

boil, so, pound, down

comet, dragon, liver, salad, denim

total, ever, student, basic, demon, vital

apron, elude, Ethan, Owen, ideal, usurp

inside, nearly, absent, unicorn, degrade, tripod

advance, offense, fence

gripped, planned, melted, batted, handed

sweeping, boiling, thinning, flopping, biking, dating

rapper, saddest, finer, bluest, funnier, silliest

easily, busily, massive, active, arrive, wives

keys, monkeys, armies, carried

action, section, musician, racial, crucial, nuptials

brittle, pickle, carbon, dormer

parcel, decent, gem, urge, badge

lose, sugar, nature, sure

graph, Phil, then, moth

bomb, thumb, gnat, gnome, high, sign

whip, whirl, echo, ghoul, knee, knob

could, calf, folk, hustle, listen, wrist

alone, bread, bear, chief, young, squaw, swan, waltz, word

decision, exposure, gigantic, polarize, occupant, quarantine

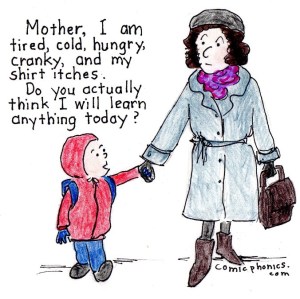

If you want to help your child learn to read, one of the best things you can do is not to let him guess. Most words can be deciphered if the student has a phonics background.

Also, don’t let your child depend on pictures for meaning once the child starts to read. Most adult reading material is not accompanied by graphics. Students must learn to gain meaning from the text alone.

If you have decided to help your child read this summer, good for you. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to help your child read better. Years of research show that the best way to teach reading is to start with letter sounds (phonemes) and then to combine those letter sounds into words (phonics). If you do this in a systematic way, such as following the four-part sequence I describe above, your child will learn to read.

4. Exceptions. These include words with silent letters (gnaw, lamb), words from other languages (debris, cello), and words which fit no pattern (business).

Ask your child to read the words in the pretest below. Each row across tests a particular phonics skill. If you child hesitates at all, that is the place to begin teaching him or her phonics. I will talk more about how to teach these four groups of phonics skills in my next blog.

Phonics assessment

bad, hem, fit, don, pug, am, if, lass, jazz

lock, Mick, bills, cliffs, mitts, catnip, Batman

grand, stent, frisk, stomp, stuck

chuck, shun, them, branch, brush, tenth

star, fern, birds, fork, purr, actor, doctor, victor

muffin, kitten, collect, pepper, gallon

complex, helmet, falcon, napkin, after

tantrum, muskrat, constant, fulcrum, ostrich

skate, bike, Jude, mole, dare, shore, tire, pure

need, cheer, aim, hair, bay, pie, boat, oar, Joe, low, soul

fruit, few, child, blind, fold, colt, roll, light, high

earn, worm, rook, pool

fault, claw, all, chalk, Walt

boil, so, pound, down

comet, dragon, liver, salad, denim

total, ever, student, basic, demon, vital

apron, elude, Ethan, Owen, ideal, usurp

inside, nearly, absent, unicorn, degrade, tripod

advance, offense, fence

gripped, planned, melted, batted, handed

sweeping, boiling, thinning, flopping, biking, dating

rapper, saddest, finer, bluest, funnier, silliest

easily, busily, massive, active, arrive, wives

keys, monkeys, armies, carried

action, section, musician, racial, crucial, nuptials

brittle, pickle, carbon, dormer

parcel, decent, gem, urge, badge

lose, sugar, nature, sure

graph, Phil, then, moth

bomb, thumb, gnat, gnome, high, sign

whip, whirl, echo, ghoul, knee, knob

could, calf, folk, hustle, listen, wrist

alone, bread, bear, chief, young, squaw, swan, waltz, word

decision, exposure, gigantic, polarize, occupant, quarantine

If you want to help your child learn to read, one of the best things you can do is not to let him guess. Most words can be deciphered if the student has a phonics background.

Also, don’t let your child depend on pictures for meaning once the child starts to read. Most adult reading material is not accompanied by graphics. Students must learn to gain meaning from the text alone.

If you have decided to help your child read this summer, good for you. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to help your child read better. Years of research show that the best way to teach reading is to start with letter sounds (phonemes) and then to combine those letter sounds into words (phonics). If you do this in a systematic way, such as following the four-part sequence I describe above, your child will learn to read.