It matters, according to research. You should start with teaching her “the code,” that is, the connection between the sounds of the English language and the letter symbols we use to mean those sounds. Here’s how. (Look for more information on all these ideas in previously published blogs at comicphonics.com.)

First, make sure she can pronounce all 42 sounds of English. Listen to how she pronounces everyday words and make sure she is saying the sounds correctly. Help her with pronunciation.

First, make sure she can pronounce all 42 sounds of English. Listen to how she pronounces everyday words and make sure she is saying the sounds correctly. Help her with pronunciation.

- Then connect sounds with letter symbols, a few at a time. Start with the beginning sounds of a few key words such as the child’s name, m for mom, d for dad, b for baby. Help her to hear those sounds in the beginnings of other words. For example, if you are pouring her milk, ask her what sound milk begins with. Then show her an “m” and explain that is how we show that sound.

- Beginning sounds are always the easiest to hear, so focus on them.

- Help her to write the initial of her name and a few other meaningful letters.

Since each vowel has many sounds, teach her to associate each vowel with a word and an image that begins with a “short” vowel sound such as apple, egg, igloo, octopus and umbrella. Later, she can compare the vowel sounds in new words to those vowel sounds.

Since each vowel has many sounds, teach her to associate each vowel with a word and an image that begins with a “short” vowel sound such as apple, egg, igloo, octopus and umbrella. Later, she can compare the vowel sounds in new words to those vowel sounds.

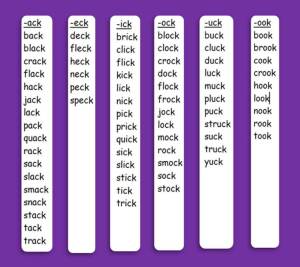

- In speaking, start putting letter sounds together to form one-syllable short-vowel (CVC) words she knows, like “cat” and “dog.” When she can hear how words are formed (phonics) by combining sounds, use letter tiles to show her what the combining of sounds in words looks like using letter symbols.

- When you are reading stories to her, point out words she might be able to decipher, and help her to sound them out.

- When she knows most of her sound – letter matches, she is ready to start reading books which use one-syllable, short-vowel words. Unfortunately, few good ones exist. We at comicphonics.com have written five humorous books for new readers. (See the links to the right of this blog.) Your librarian can point out where other books are shelved, but many labeled “first” readers contain difficult words. Margaret Hillert has written some good beginning books, and so has Dr. Seuss. Good illustrations can help the child figure out the meanings of difficult words, but she will probably need your help as she begins.

Figuring out the code of written English is how a child begins to learn to read. There are lots of commercial methods to do this, but the best I have found is the Explode the Code series. Children find its combination of goofy pictures and sequenced phonics instruction fun.

Later you can focus on other aspects of reading including fluency and comprehension. But the place to begin is demystifying the code by connecting the sounds of our speech to individual letters and pairs of letters, and then combining them to form words.