Choral reading is reading aloud as a group, much like a choir reads the words and sings them together aloud. It is commonly done in lower grades and in ESL classes for several reasons:

- Children who are less skilled readers can listen to the more skilled readers beside them, and can model their reading after their classmates’ reading. In particular, less skilled readers can hear fluency (emphasis of certain words or syllables, pauses for punctuation, speeding up and slowing down) which less skilled readers might read too slowly to use correctly.

- Children who stumble over sight words can hear them pronounced and can say them aloud without drawing attention to themselves. ESL students can hear correct inflections and can practice copying them.

- Less skilled readers can practice aloud with anonymity, their mistakes or hesitancies masked by the reading of the larger group.

- Children who are poky readers, who stumble while trying to decode words, will gain comprehension which they sometimes miss.

- Choral reading is fun for children.

Certain kinds of books or readings work well for choral reading.

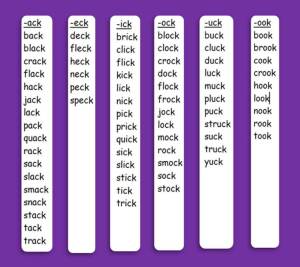

- If a book has a rhyme pattern, or a predictable rhythm, it can be a good choice. A poem or nursery rhyme makes a good choral reading selection.

- If the book is short, so that it can be repeated several times in a few minutes, it can be a good choice.

- If the book is at the reading level of the less skilled students, it can be a good choice.

- If less skilled readers are familiar with the rhyme or story, it can be a good choice.

Working one-on-one with a student, the parent and student can read aloud together from the same page. If the choral reading happens in a classroom, each student should have a copy of the text or be able to see a Big Book which everyone can use. Usually the adult reads first while the students follow along, pointing their fingers at the spoken words. Then the student joins in. The student might feel more comfortable if the adult reads with gusto, drowning out the mistakes of the beginning reader. As the selection is reread, the adult can read less loudly, allowing the child’s voice to be heard. Rereading the selection several times over several days is a good way to help the less skilled reader to remember the words or to figure them out quickly.