It’s September, which means a new school year, which means a new set of kindergarteners learning to read.

Where to start? I have hundreds of blogs on this website showing how to teach reading. But in general,

Start with prereading skills. These include knowing how to hold a book, which cover is the front, reading from left to right and from up to down, and knowing that text means words.

Teach that letters are symbols of sounds, with each letter representing a different sound. Of course, some letters represent more than one sound, and some letter pairs represent a single sound, but that news can wait.

Help the child memorize several consonant/sound pairings and one vowel/sound pairing (usually the letter A). The child does not need to know every letter sound to start reading. Learn a few, and while you make words, learn a few more. And knowing ABC order is not important at all at this point.

Make sure the child realizes that joining letters together forms words. Create two- and three-letter words with the letters the child knows. I recommend using letter tiles, saying aloud the letter sounds and moving them closer together until they create words.

Help the child learn one-syllable, short-vowel words which follow the rules. “Golf,” yes. “Half,” no.

Help the child learn often used “sight” words necessary to form sentences. Lists are online.

Cover adding S for the plural; double F, L, S, and Z to make a single sound at the end of some words; CK to make the sound K; blends at the beginning of words; and blends at the ends of words. By now it’s winter break or maybe spring break depending on how often your child works on reading and how ready your child is.

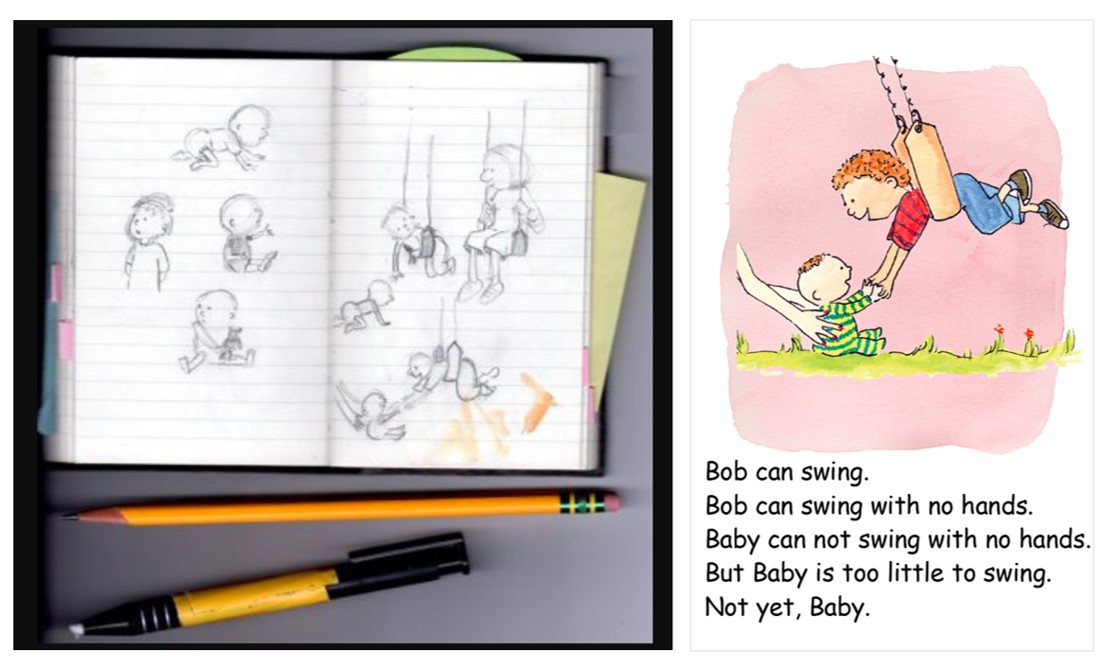

Supplement what your child is learning with small early-reading booklets. You will find many publishers.

Review what the child has learned at each lesson. One way is to buy reading workbooks. The quality varies greatly. I recommend Explode the Code because it follows the pattern I have outlined above and because children like the silly drawings. (I have no connection to the publisher of that series.)

Keep reading to your child to instill a strong interest in reading.

Teach long-vowel, single-syllable words containing silent E and double vowels. Expect backsliding here from many children.

By now your child is more than ready for first grade. Check with your state education department’s standards for kindergarten to be sure you have covered everything. If you haven’t, or even if you have, keep at it over school breaks, including summer break.

And check back issues of my blog. If I haven’t covered a topic you are looking for, let me know and I will.

Little children who are learning about sounds in words move from larger units of sound—phrases and words—to smaller units of sound—sounds within words and syllables. Adults hear “On your mark, get set, go,” but a two-year-old hears “Onyourmark, getset, go.” Children need to hear distinct sounds within words and to reproduce those sounds properly before they start pairing sounds with letters.

Little children who are learning about sounds in words move from larger units of sound—phrases and words—to smaller units of sound—sounds within words and syllables. Adults hear “On your mark, get set, go,” but a two-year-old hears “Onyourmark, getset, go.” Children need to hear distinct sounds within words and to reproduce those sounds properly before they start pairing sounds with letters. A good example of this is when children learn the ABC song. Most three-year-olds can start the song with A-B-C-D. . .E-F-G-. . .H-I-J-K . But when they get to L-M-N-O-P they sing L-um-men-oh-P or M-uh-let-O-P. They don’t hear L-M-N-O as distinct sounds.

A good example of this is when children learn the ABC song. Most three-year-olds can start the song with A-B-C-D. . .E-F-G-. . .H-I-J-K . But when they get to L-M-N-O-P they sing L-um-men-oh-P or M-uh-let-O-P. They don’t hear L-M-N-O as distinct sounds.