Did you know that that even Dr. Seuss books have irritated readers so much that they tried to get them banned from school and library shelves?

See if you can identify why the books below, usually read in elementary and middle grades, were challenged and in some cases banned. Answers will appear at the end. (Some questions have more than one correct answer.)

1. Why did a patron of the Toronto, Canada, Public Library want Hop on Pop by Dr. Seuss banned in 2014? (It wasn’t. Phew!)

a. imperfect rhymes

b. too dark a theme for little children

c. encouraging of young children to use violence against their fathers

2. Why did patrons of the Vancouver, Canada, Public Library want If I Ran the Zoo by Dr. Seuss banned in 2014? (Again, reason prevailed.)

a. Vancouver doesn’t have a zoo.

b. Illustrations show Asians with slanted eyes.

c. Illustrations of snakes were too scary for children

3. Why did two parents of the Brainerd, MN, School District want John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men banned?

a. Japanese people were referred to as Japs.

b. Jesus Christ was used as a curse word.

c. The n-word (the actual word) was used to describe African Americans.

4. Why were the Harry Potter books by J. K. Rowling challenged hundreds of times by religious groups within the first two years of publication?

a. violence

b. occult/Satanic themes

c. anti-family themes

5. Why was The Giver by Lois Lowry ranked eleventh for books most frequently asked for removal from schools from 1990 to 2000? (It was removed about one-third of the time.)

a. violence

b. too dark a theme for children

c. too few women characters

6. Why was To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee challenged in Eden Valley, MN, in 1977 and temporarily banned?

a. It used the words “damn” and “whore lady.”

b. It depicted a bigoted aunt who expressed her views using the n-word.

c. The Humane Society objected to the way a rabid dog was killed.

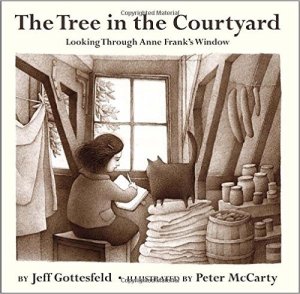

7. Why was Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank challenged but not banned by the Northville, MN, middle schools in 2013?

a. too realistic description of Nazi atrocities

b. too realistic description of a girl’s anatomy

c. The diary was published without the author’s permission.

8. Why did some parents in Liberty, SC, in 2013 want No Fear Shakespeare; Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare banned?

a. suicide

b. underage marriage

c. mature sexual theme

Google “banned books” and you’ll see that the list of banned books is long, though fortunately, most books’ placement on the list has been short-lived. Eighty years ago the Nazis had book-burning bonfires, but today Europeans read those same books unimpeded. Luckily, we live in a time of the internet, when it’s almost impossible to ban books any more.

- c

- b

- a, b, c

- a, b, c

- a, b

- a

- b

- c

Provide necessary supplies. Sharp pencils, erasers, pens, colored pencils, notebook paper, a tablet or laptop, and a good dictionary should be at hand.

Provide necessary supplies. Sharp pencils, erasers, pens, colored pencils, notebook paper, a tablet or laptop, and a good dictionary should be at hand.