Wordless picture books (books with no words except for the titles) and almost-wordless books (books that repeat the same word, phrase or sentence over and over) are a category of picture books that began in the 1960’s but have grown increasingly popular. There are several kinds:

- Concept books. These include ABC books, counting books and pictures for infants to identify. They also provide pictures of everyday objects for ESL students to identify.

- Books related by a theme or a sequence. These books show illustrations that are related, but not by a story line. Books showing different kinds of trucks, or pictures of how the seasons change, or pictures showing a bedtime routine are examples.

- Books showing expository content. These books might explain how a caterpillar becomes a butterfly or show all the protection a football player puts under his uniform.

- Books showing visual games. Interaction is required to find a hidden object or to find subtle differences in two nearly identical pictures. The reader might need to point to the hidden item, or circle differences in pictures.

- Story books. These might show simple or complicated story lines.

I assume the books you are asking about are story books. Why have stories without words? Let’s start by talking about two-year-olds.

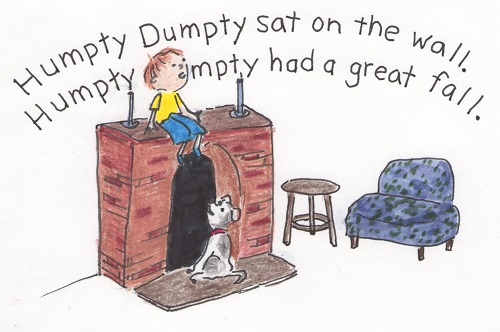

Click on the picture to enlarge it.

Kids who have just turned two are probably not aware of “story” as we know it, even though they might have been read to a hundred times. When they look at a picture book, they see individual pictures, not parts of a story. They might be interested in the boy on page 3 because of his glittery sneakers, or they might notice the funny expression on a dog’s face. When they look at page 4, two-year-olds probably are not aware that events on page 3 have caused events on page 4. The picture book is not so much a story with a beginning, middle and end for such young children. Rather it is a collection of fascinating pictures.

For such children, does it matter if there is text on page 3 or page 4? Probably not. They are getting their meaning from the pictures.

Does it matter if the adult reads the accompanying text aloud or not? Probably not to the two-year-olds. The words give just one meaning—that of the author. But the children are more interested in gaining their own meanings. They pick up on their own clues and focus on what is important to them. You have probably had the situation where you are trying to finish reading a story but your child doesn’t care about the story ending. He would rather talk about one of the pictures, or leaf back through the book to see a particular picture again.

Click on the picture to enlarge it.

Yet sometime between two and kindergarten, most children realize that story books are more than a collection of fun pictures: the pictures tell a story with a beginning, middle and end. Do children need text to learn this? Probably not. As they become more sophisticated at “reading” pictures, they notice more, they make more connections, and story emerges. It is only when children begin to read words that they need words on the page.

So back to your question. What are these wordless story books for?

- With no right or wrong words to explain what is happening, these books allow for wider interpretations than a text might allow. Children can bring their own meaning to the stories.

- Research shows that parents who tell a story based on pictures only use a richer vocabulary and more complex sentence patterns than authors usually use in picture books. Children pick up on the vocabulary and become attuned to longer sentences.

- Bilingual parents can mix vocabulary from two languages to make the story meaningful for their children. Parents who don’t speak English can “read” the story in their own languages.

- Developmentally delayed children benefit from having the reader tailor the story to their level. Or they get the chance to tell the story from their own point of view, with no right or wrong perspective.

As children grow, these books have other advantages:

- Children can learn the elements of story from these books—characters, setting, beginning, middle, and end.

- Children can think creatively, coming up with various possibilities to interpret a single picture book.

- Children can learn how to tell stories orally before they have the skills to write stories down.

- By using recording devices and cameras as children “read” these stories, children can record their favorite stories to share with Grandma in Taiwan or with Mom waiting at the gate for her flight.

- Once children begin to read and write, they can write their own words for the wordless story books, and read them aloud.

- Children can use the books as models, illustrate their own stories and then supply words, perhaps dictating to an adult.

- Children can gain success in reading, like reading and feel confident reading all before they can “read” real words.

Like all books, the quality and sophistication of wordless picture books varies. A children’s librarian can point out some good ones. Or you can find lists on the web. Some classic ones include:

- A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog by Mercer Mayer

- Pancakes for Breakfast by Tommie de Paola

- Time Flies by Eric Rohmann

- Picnic by Emily Arnold McCully

- Up and Up by Shirley Hughes

- Free Fall and Tuesdays by David Weisner

- board picture books by Helen Oxenbury