Understanding the main idea of a piece of writing is probably the most important aspect of reading once children understand phonics. Yet many children struggle to find the main idea. How can we help them?

- Ask the children to read the title and any subheadings. Ask the children what those words mean. Ask the children to predict what the writing might be about.

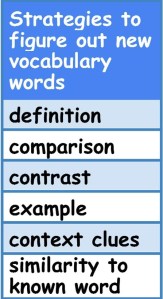

- Ask the children to look at any graphics such as photos, graphs, charts, maps, diagrams or other nontextual information. Ask the children what they have learned from those graphics. Ask them to predict what the reading might be about.

- In nonfiction, the main idea is often expressed at the end of the first paragraph. Ask the children if the last sentence of the first paragraph tells what the main idea is.

- In nonfiction, many times the first paragraph or even two or three paragraphs are a hook. They might give hints about the topic of the writing, but they might not tell the main idea. Ask the children if that is the case with what they are reading.

- In nonfiction, topic sentences often start the body paragraphs of a reading. Ask the child to read the first sentences of the body paragraphs. Are they topic sentences? If so, what is the topic that they are giving details about?

- In the last paragraph of nonfiction, the main idea is often repeated. Ask the children to read the last paragraph and to identify the main idea if it is there.

- Reading the first important paragraph (not the hook) and the last paragraph, one right after another, can sometimes help children to discover the main idea. Do both paragraphs talk about the same thing? If so, what is it?

Some children will understand immediately while others will need many, many lessons focused on the main idea. If children need more examples, more tries at figuring it out, make sure they get those extra examples and time. Figuring out the main idea will be on almost every reading test they ever take from first grade to the SATs.

But more importantly, it is a life skill which they will need.

of little children. Children do not need to be taught these words; they learn them from interacting with their caretakers and other children. In kindergarten, some of these words are called sight words. Usually these words do not have multiple meanings. Such words include “no,” “dad” and “dog.”

of little children. Children do not need to be taught these words; they learn them from interacting with their caretakers and other children. In kindergarten, some of these words are called sight words. Usually these words do not have multiple meanings. Such words include “no,” “dad” and “dog.”

Before you read:

Before you read: